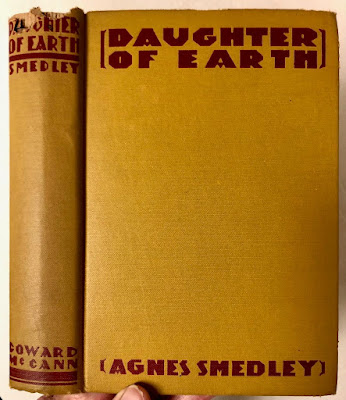

“Daughter of the Earth,” by Agnes Smedley, 1929

Agnes Smedley is a mostly forgotten left-wing American

activist and writer. She is best known

for her reporting about the Chinese revolution.

Her second book, “Battle Hymn of China,” serves as a sequel to “Daughter

of the Earth.” Until the Nazi’s closed

the paper, she reported for the Frankfurter Zeitung on the Chinese Red Army,

and met Mao, Chou En Lai and Chu Te. She

then reported for other western publications, and wrote other books about the

revolution there. She is really the

female John Reed of the Chinese revolution, and was later black-listed for this

in the 1950s.

‘Daughter of the Earth’ concerns itself with the American period

before World War I until 1927. It is a

powerfully written semi-autobiographical novel of a working-class woman growing

up in a brutal, poor and conservative society.

It is as plainly written as Maxim Gorky or Jack London might do, missing the

similes or metaphors that litter more middle-class writing. There are no ‘the sun rose like the headlight

on an on-coming train’ in this book. Her

raw emotions and anger provide the fuel which carries you through most of the

book. She is an inchoate Emma Goldman, a

political Calamity Jane, her own person.

The fictional Marie Rogers was the daughter of poor farmers in

The most striking part of this book is how it describes a young

woman trying to keep her dignity in a society that just sees her as a sexual

target, a baby-maker or a weakling.

Marie has to fend off the advances of various drunks and those men drunk

on their own personalities. She avoids sex like the plague because she knows it

will lead to having a houseful of kids, beatings and misery. She hates marriage because she wants no man

telling her what to do. She is forever

being thought of as a prostitute or loose woman because she is not

married. The Christian religion is a

foreign thing to her, and she knows it to be hostile to the poor. She knows that only earning her own living

will give her independence. She dresses

atrociously, from both poverty and choice.

She carries a small gun and knife and travels from town to town

searching for knowledge – attending various schools, becoming a hardscrabble

teacher, trying to find someone she trusts.

She meets the various leftists of the day – working-class IWW members,

parlor Socialists, middle-class liberals and a few Communists, and has a natural

class feel for all of them.

Marie also feels the guilt of someone who wants to help her

family, but basically abandons her siblings and relatives to pursue her

life. There is a lot of ‘I’ in Marie,

which might have been her salvation. Her

emotions are always on the surface, she sees insults easily and deeply, she is

not afraid to tell people what she thinks without sugar-coating it. What she sees among the majority of working

people is that they do not have a clue why the world is the way it is. Food, drink, warmth, sex, money and music are

sufficient balms and concerns. Yet the

miners strike time after time against the bloodthirsty mining concerns. She slowly comes to a political consciousness

through study, her contact with leftists and the very material roots of her

miseries.

Marie eventually moves to New York where she works for a

book-reviewing publication, then “The Call” – a socialist newspaper, and also,

oddly, for the Indian independence movement.

Through her work with the Indians, she is arrested and sent to the cold

Tombs Prison – which she wryly notes is very close to Wall Street. There she is starved, interrogated and incarcerated as a ‘spy.’

It is only with the end of World War I that she is released. The socialists in New

York can’t understand why she would work for nationalist Indians,

but she (as Lenin would also have agreed) argues that freeing India Denmark

This book follows on the heels of the earlier American working-class

feminist classic, “Life in the Iron Mills.”

Novels by working-class people are rare, and ones that are political are

rarer still. This book is unique in its

class and feminist stance. It portrays a

lonely and tough female personality that one rarely encounters, except,

perhaps, in the pages of books. It is

our way of meeting Agnes Smedley herself, a real person.

And I bought it at May Day Books used/cutout book section.

Red Frog / February 23, 2013

No comments:

Post a Comment