“Left-Wing Melancholia – Marxism, History and Memory” by Enzo Traverso, 2016

This book looks at the situation of the Left after what Traverso considers a world-historic defeat of communism. That consists of the fall of the bureaucratic 'socialist' USSR, the central-eastern European workers' states and the degeneration of the mass Socialist and Communist parties in various countries. Gramsci's 'war of position' was posed in the 1920s and Traverso considers it lost. Traverso seems to be unaware of present vital efforts to keep Marxism alive, but lets hear what he has to say. Traverso dates the change in socialist attitudes to the 1980s and 1990s. In the 1970s and before Left victories over colonialism, apartheid, various dictators, capitalism and the U.S. defeat in Vietnam gave the Left an optimistic, emancipatory boost. After this period he considers the Marxist goal of a human 'utopia' off the table. The future now no longer exists in his view, just an endless 'presentism' and the dead hand of the reactionary past.

These defeats take the form of a Leftist melancholia, which in Traverso's survey is part nostalgia, part tragedy, part defeat, part memory, part history, part sorrow, part martyrs, part tradition, part inspiration. Victims became the special focus in this vein, especially the memory of the Holocaust, slavery or Jim Crow, the Red Scare, Shirtwaist or the hanging of Joe Hill in the U.S. Agency and Left victories are forgotten in the general warp and weave - except in the small circles of the hard left. My main issue with this book is 'why'? Is the book only an elegiac and academic description of the present or does it posit some move forward beyond melancholia?

Traverso tracks how defeat has always been a part of the Marxist revolutionary myth. Supposedly you 'lose until you win.' Defeats and heroism are remembered in order to give historic impetus to further class struggle and victories. The 1848 Paris revolt and the later 1870 Paris Commune especially played that role; the defeat of 1905 as a 'dress rehearsal' for the Russian revolution of 1917; the crushing of the various 1919 revolutions in Europe inspired the revolts of the '30s and '40s, including the Chinese Revolution. In our time the death of Che Guevara, the assassination of Malcolm X, the crushing of the Panthers, the overthrow of Allende all 'infuse' this myth. Prior to the 1990s a certain teleological, optimistic certainty about 'the future is ours' was more common among many leftists. Earlier, in the face of fascism, both Luxemburg and Trotsky had spoken of 'socialism or barbarism.' That seems to be our present 'melancholic' situation. The environmental situation does not encourage optimism either, though it destroys 'free market' logic in spades.

Traverso hints that actual socialists must embrace both the past, present and future. However it is obvious that many far leftists dwell in the past in various ways, and have no conception of how the future will actually arrive. Traverso ignores China, but some find their 'optimism' in the CCP and state-led development of China. It's a thin reed that does not translate in a mass way even in China. Nor does China make any effort to export 'revolution' and actually never has. Others cling to anyone who opposes the U.S., no matter from what position – authoritarian, leftist, theocratic, conservative, Republican or fascist. This kind of reflexive 'anti-imperialism' abandons a socialist future or any actual plan to get there. It is another 'melancholy' symptom.

Cultural Arty Facts

To make his points other than through voluminous and erudite quotes, Traverso looks at various Italian communist neo-realist films, along with political ones from Latin America. As he puts it “Defeat had turned communism into a realm of memory.” Pontecorvo's 'Battle of Algiers' and the anti-colonial film 'Burn' come in for special attention. Others are the post-Soviet film about central Europe, “Ulysses Gaze;” the French film, “A Grin Without a Cat;” Ken Loach's “Land and Freedom” about the Spanish Civil War and films about post-Allende Chile – in particular “Santa Fe Street” and “Nostalgia for the Light.” He brings up C.L.R. James' analysis of Moby Dick as Melville's 1851 parable about capitalism leading to totalitarianism. Quite prescient!

|

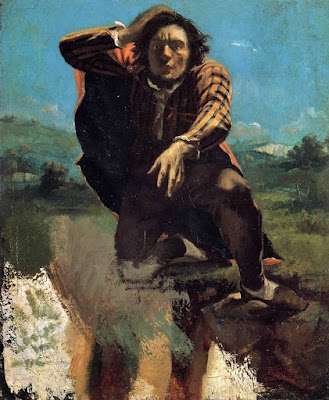

| Courbet self-portrait: Desperate Man |

Traverso looks at 1800s 'Bohemia' in Paris – at the time the marginal realm of anti-government plotters, anarchists, dissident artists and intellectuals, petty criminals, drinkers and layabouts who were neither part of the intelligentsia nor full-on lumpens. Marx was mostly hostile to this strata, considering them basically lumpen-proletarians, but Traverso sees this sub-cultural strata splitting or shifting based on the times and political situation. Bohemia went on to be called the Lost Generation, the Flappers and Jazzmen, the Surrealists, the Existentialists, the Beats, the Hippies, the Punks, then the Rappers, Hip-Hoppers and the Hipsters. But these counter-cultural strata changed or were crushed, to the point that a real Bohemia is invisible now. The real Bohemia has become a semi-proletarian underground of marginalized persons with no public face. It's public U.S. face – hipster and hip-hop - has been commodified and captured, another melancholic development.

Traverso chooses to highlight Courbet, a Bohemian utopian-socialist painter who put 'le peuple' and symbols of the people at the center of his art, an art that mourned the failed revolutions of 1848 and 1871. Baudelaire, Heine, Flaubert and Herzen all reflected these bloody defeats as well. Baudelaire, the author of “La Fleurs de Mal,' took part in the 1848 revolt, manned a barricade and escaped the slaughter. But Baudelaire was also an anti-Semite, reflecting the Janus-faced nature of this unstable 'declasse' artistic strata. This strata eventually produced revolutionaries like Breton and outright fascists like Celine and Marinetti. As Traverso points out Marx, Benjamin, Lenin and Trotsky, along with Greenwich Village's John Reed, all lived unstable 'bohemian' lives for a long time.

Colonialism and Imperialism

Traverso places an emphasis on how Marx's situation in Europe in the 1800s conditioned his world-view. While Marx understood capitalism and traced the roots of colonialism, he was not the theorist of imperialism and the revolutionary role of national-democratic struggles as was Lenin. Marx was critical of Toussaint l'Overture, the Mexican Revolution's Zapata and Villa and Latin America's Simon Bolivar. These had to wait for later Marxists to trace their emancipatory role or to lead national-liberation and anti-dictatorial struggles. He makes the point that Marx's concept of an unchanging 'Asiatic mode of production' was an approximation regarding relatively unknown economies to Europeans, mostly based on Morgan's work. Later Marxists have refined that analysis of early production economies. Traverso, a French academic, does not believe that capital played a revolutionary role in developing the forces of production. What role did it play then? A continuation of feudalism? Marx excoriated colonialism over its violent and exploitative 'primitive accumulation of capital' in Ireland, in India, in Peru and the slave economy of the U.S. Yet why this discussion is in a book on 'left-wing melancholia' I do not know.

The connection seems to be the development of 'Western Marxism” (a misnomer) and post-colonial theory. The Frankfurt School, in the face of the triumph of bureaucracy in the USSR, advent of fascism in Germany and Italy and the decay of the European Left reflected a retreat from 'classical' Marxism into a cultural refuge. Their product is what the Republicans call 'cultural Marxism.' Similarly “post-colonial theory' grew out of opposition to classical Marxism based on the collapse of the Soviet bureaucracies. Absent any class and economic analysis, post-colonialism diverted the struggle against capitalism into an ethnic conflict, even when using the term 'intersectional.' The two – post-colonial theory and 'Western' Marxism - finally united in the university academy, a fusion we live with to this day. I guess this is melancholy as theory. It also has the smell of revolutionary defeat.

Traverso looks at the sadness of Benjamin and Adorno in the face of the twin defeats of the 1940s, fascism and the brutal bureaucracy in the USSR. They argued over jazz, over Surrealism, over culture, over how to defeat fascism, over capitalism. Benjamin thought Marxism had to become 'messianic' – a Red version of liberation, a religio-secular movement. Traverso then moves on to Daniel Bensaid, a younger French Trotskyist involved in May-June 1968, who later played a role as a bridge between different Marxist currents. Bensaid embraced both a utopian vision and Benjamin's messianic method - or something like that according to Traverso. This is the kind of vague direction that makes you yearn for 'classic' Marxism.

At the end Traverso has no answer to Left melancholia, so this is purely an analysis of the present and near past and nothing else. In its own way it is an academic product of that tendency. Not that there is nothing to mourn about. But as Joe Hill pointed out: “Mourn but Organize!”

Prior blog reviews on this subject, use blog search box, upper left, to investigate our 17 year archive, using these terms: “One Way Street” (Benjamin); “Did Someone Say Totalitarianism?”(Zizek); “The Melancholia of the Working Class,” “How to Read a History Book,” “How Will Capitalism End?” “A Walk Through Paris,” “Marxist Criticism of the Bible,” “Transatlantic,” “Marxist Theory of Art.”

May Day Books has many volumes on Left cultural and theoretical writing. Educate yourself! I got this from the UGA Library.

Red Frog / February 22, 2024

No comments:

Post a Comment