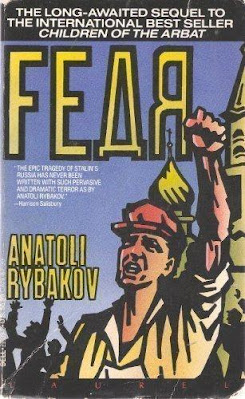

“Fear” by Anatoli Rybakov, 1990

This book, unlike any other,

takes you into the heart of the purge trials of the 1930s in the USSR after the assassination of Kirov.

It does not contain descriptions of camps or mass deportations or

killings, but a personal story of those involved in the trials, as well as the

civilians affected by the atmosphere of death and uncertainty. The purges ultimately went far beyond the

public trials themselves and insinuated themselves into every facet of social

life. It is a sequel to Rybakov’s Children of the Arbat. It is about fear – of the government, of your

neighbor, of your family, of yourself. Rybakov’s

analysis is that Stalin had Kirov

assassinated, and used that as an excuse to purge opponents and rivals. It is written as a semi-fictional account of

the period, interposing the lives of the fictional characters with factual descriptions

of real events and people.

The book continues the story

of Sasha Pankratov, a student who is exiled to Siberia for 3 years for making a

comment in a school newspaper that is seen as ‘politically subversive’ by the

NKVD. The book is centered in Moscow, and includes many

references to the streets and squares of that city. The fictional characters include an art

critic who becomes an informer, even on people he has known since childhood

like his barber. An operative in the

NKVD who does interrogations and gets confessions out of ‘suspects,’ but has

secrets of his own. Sasha’s mother and a

young woman, Varya, who both worry and pine after Sasha. Working class exiles

who can no longer live in Moscow or Leningrad. An old census taker and family friend who

finds that many people are missing in the census. A high school teacher who is expelled from

the Party, fired, then arrested. A loyal

Communist who suddenly realizes she is a target and escapes to Vladivostok upon the urgings of her sister. A woman who marries a rich foreigner and

leaves for Paris. Relentless thugs working for the NKVD. Arguments within families over being arrested

or suspected of being a subversive for any slip of the tongue or association. Pro-German spies working for the NKVD’s

foreign section. Doctors who see their

fellow doctors disappearing, and CP leaders and workers disappearing.

These ‘fictional’ stories

are interspersed with chapters dominated by Stalin as he plans the show trials

for Kamenev, Zinoviev, Radek, Bukharin, Tukachevsky and others. Rybakov paints a pretty accurate psychological

portrait of Stalin embedded in real

historical detail. Every fabricated

confession – through threats to family, various forms of torture, lying

promises that the confessor will not be shot – is based on a conspiracy theory. It is that the ‘Trotskyites’ are at

the head of a vast ‘fascist’ conspiracy to undermine ‘the Party.’ In this, the “party” has replaced socialism, the working class or revolution as the most important thing in the USSR. That ‘party’ has actually devolved to control

by Stalin and a few of his closest allies.

Many of the real CPers voting to execute their real comrades are also

later killed. Even the Cheka and NKVD

are purged, to make way for new cadres controlled by Stalin and the apparatus

of fear. Stalin calls this ‘the cadre

revolution.’

|

| Other Cover |

This is a powerful and long

book that takes you inside a situation you never want to be in. Many respected cultural figures were forced to applaud the purges. Ultimately to avoid imprisonment or poverty

or death, it makes cowards of everyone, even Sasha Pankratov. He serves his sentence only to return from

exile into a country where nearly everyone is afraid, and so conforms and

follows orders. That is the ultimate

goal of fear.

Addendum: For the few people I know who

are still nostalgic for Stalin. Nearly all were recruited through Maoism in the 1960s and

1970s, which had Stalin in its pantheon.

At the time, China

was a revolutionary beacon, which was quickly extinguished, especially after

the block with the U.S. After Che,

Cuba has been

unable to export its revolution and stays frozen in time defying

capitalism. Vietnam thankfully won its war and

now peacefully manages its mixed economy.

The USSR

and the workers’ states in central and eastern Europe are no more, as

counter-revolution triumphed. So the

major ‘material’ bases for the past credibility of Stalinism as some kind of alternative has mostly collapsed, though not everywhere. This ignores, of course, any separate

political or economic or historical facts, which I won’t get into here. Because of this disappearing history,

young radicals the world over will not be drawn into Stalinism in any numbers.

And I got it at the Library!

Red Frog

April 26, 2018

No comments:

Post a Comment